When languages think differently

What Spanish, Italian, and English idioms reveal

Have you ever felt that when you're learning a language, you're not just picking up new words and grammar rules, but also starting to see the world a little differently?

Maybe you struggle to express something that seems simple in your first language, or you notice that your new language makes you pay attention to details you'd normally ignore. You're not imagining it. Languages can indeed differ in how they "package" or "organize" reality, and learning a new one can influence how you think.

This goes deeper than just having different words for things. It's about the underlying ways speakers are prompted to perceive, analyze, and talk about the world around them. When you learn a language, you're not just memorizing new labels for familiar concepts. You're developing new ways of thinking about those ideas.

Take something as simple as drinking containers. English speakers call a disposable coffee container a "paper cup" and a transparent drinking vessel a "glass", using completely different base words ("cup" vs "glass") that reflect both function and material. Spanish speakers call both a "vaso", whether it's "vaso de papel" (paper glass) or "vaso de vidrio" (glass made of glass), because they focus on shape: drinking containers without handles are "vasos" regardless of what they're made of. Each language is guiding speakers to notice different aspects of the exact same objects.

These conceptual differences become even more fascinating when you look at similar languages. Spanish and Italian are a perfect example. You'd expect closely related systems to organize ideas in nearly identical ways, and often they do. But despite sharing Latin roots and countless cognates, these sister tongues reveal interesting variations in how they structure thoughts about everyday experiences.

Why this matters if you're learning a language

For language learners, these differences can create some of the most interesting discoveries and some of the most persistent challenges. You might find yourself constructing perfectly grammatical sentences that somehow sound "off" to native speakers, or your examples feel slightly awkward even when they're technically correct. The grammar is right, the vocabulary is spot-on, but something just feels unnatural.

What's often happening is something called conceptual transfer. You're unconsciously applying your first language's way of organizing reality to your second language's words.

So how exactly do languages organize reality differently?

One key way is through conceptual metaphors—patterns each language uses to make sense of abstract ideas by connecting them to concrete, physical experiences. We understand complex concepts like time, emotions, or relationships by relating them to things we can actually touch, see, and move through the world.

These metaphorical patterns show up everywhere, but they're especially visible in everyday expressions. Take "make a decision" in English—it suggests crafting or creating something new. But Spanish and Italian speakers "take" decisions (tomar una decisión - prendere una decisione), which feels more like selecting from existing possibilities.

Or consider saying a relationship is "on the rocks". It might seem completely random, but it connects to how we think about life as a journey. When you're "on the rocks", you're in trouble, like a ship that's hit dangerous obstacles.

With closely related languages like Spanish and Italian, the abundant similarities can actually make the subtle differences harder to spot. But research shows that understanding the logic behind these metaphorical connections helps you remember and use idiomatic expressions more naturally. So we're going to compare common Spanish and Italian idioms, contrast them with the English versions, and unpack the thinking behind them. Once the underlying logic clicks, the expressions themselves will be much more likely to stick (conceptual metaphors very much intended).

Spanish, Italian, and English examples

Let's look at how everyday expressions actually demonstrate these conceptual differences. We've chosen a mix of serious and playful examples to show how these metaphors work across all kinds of human experiences.

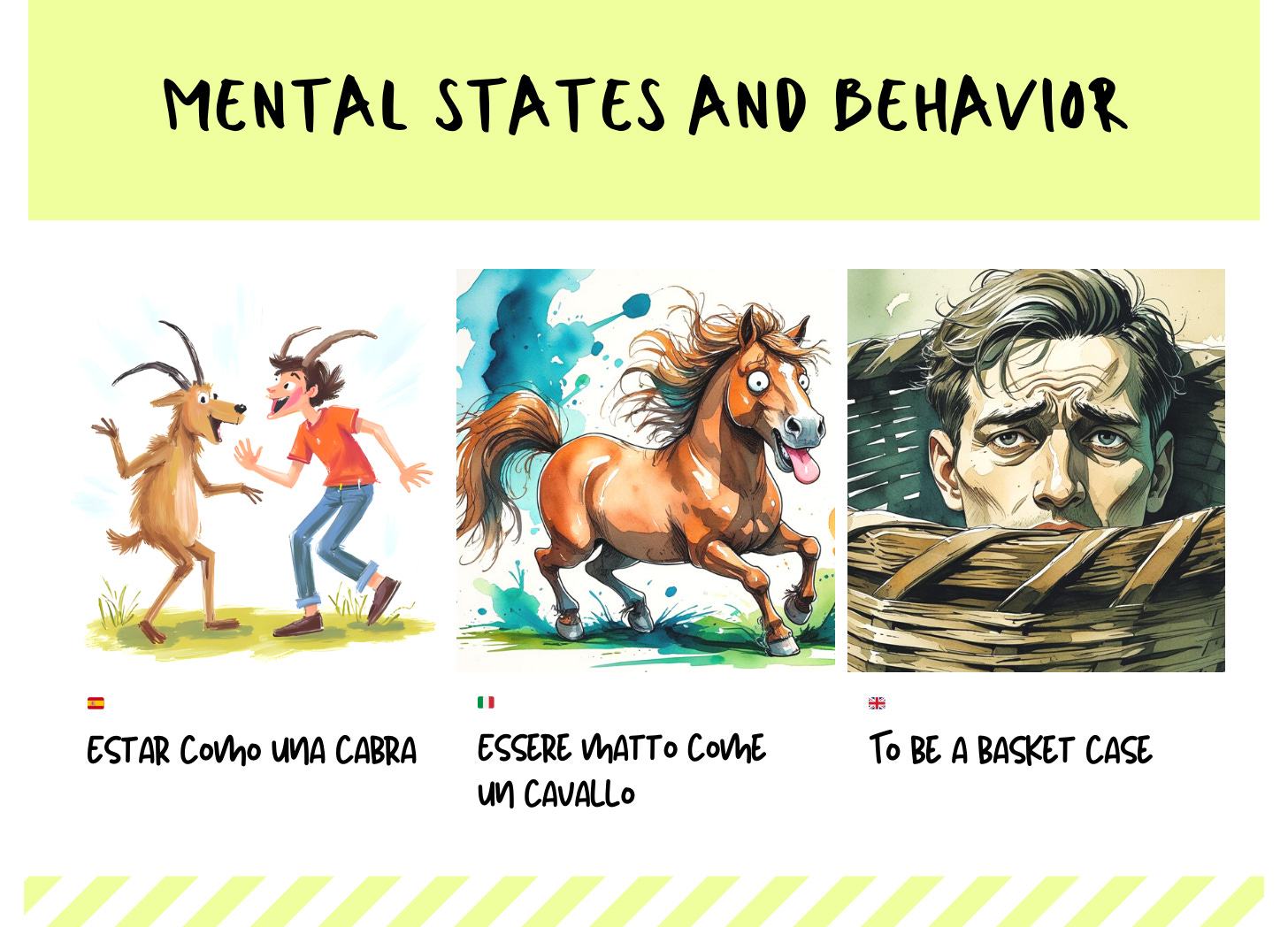

Mental states and behavior

Spanish: Estar como una cabra (‘To be like a goat’)

Ever watched a goat suddenly decide to climb something completely inappropriate? Spanish speakers use this unpredictable goat behavior to describe someone acting erratically.

The metaphor: Unusual mental states are like animal behaviors.

Why goats? They're famously unpredictable, changing direction suddenly, climbing where they shouldn't, doing unexpected things.

The tone: Humorous. A playful way to comment on someone's odd behavior.

Italian: Essere matto come un cavallo (‘To be mad like a horse’)

The metaphor: Similar to the Spanish one.

Why horses? Horses aren’t generally considered unpredictable animals, but this might refer to terrified or untamed horses.

English: There are various versions of this expression

Common idiom: To be a basket case

Origin: This idiom came about at the end of the First World War, to describe soldiers who had lost all 4 limbs and had to be carried about in a basket. Apparently, there weren’t any documented “basket cases”. It was just a post-war myth, but the expression stuck. Although the original meaning referred to a physical state, it changed over time to the current meaning, related to unusual, unpredictable psychological ones.

Other variations: To be nuts/bonkers, to be off your rocker.

Interesting note: There is an expression in English, “to act/play the goat”, but the meaning is a little different to the Spanish “estar como una cabra”. If you act/play the goat (or fool), you behave a bit silly, like “hacer tonterías”.

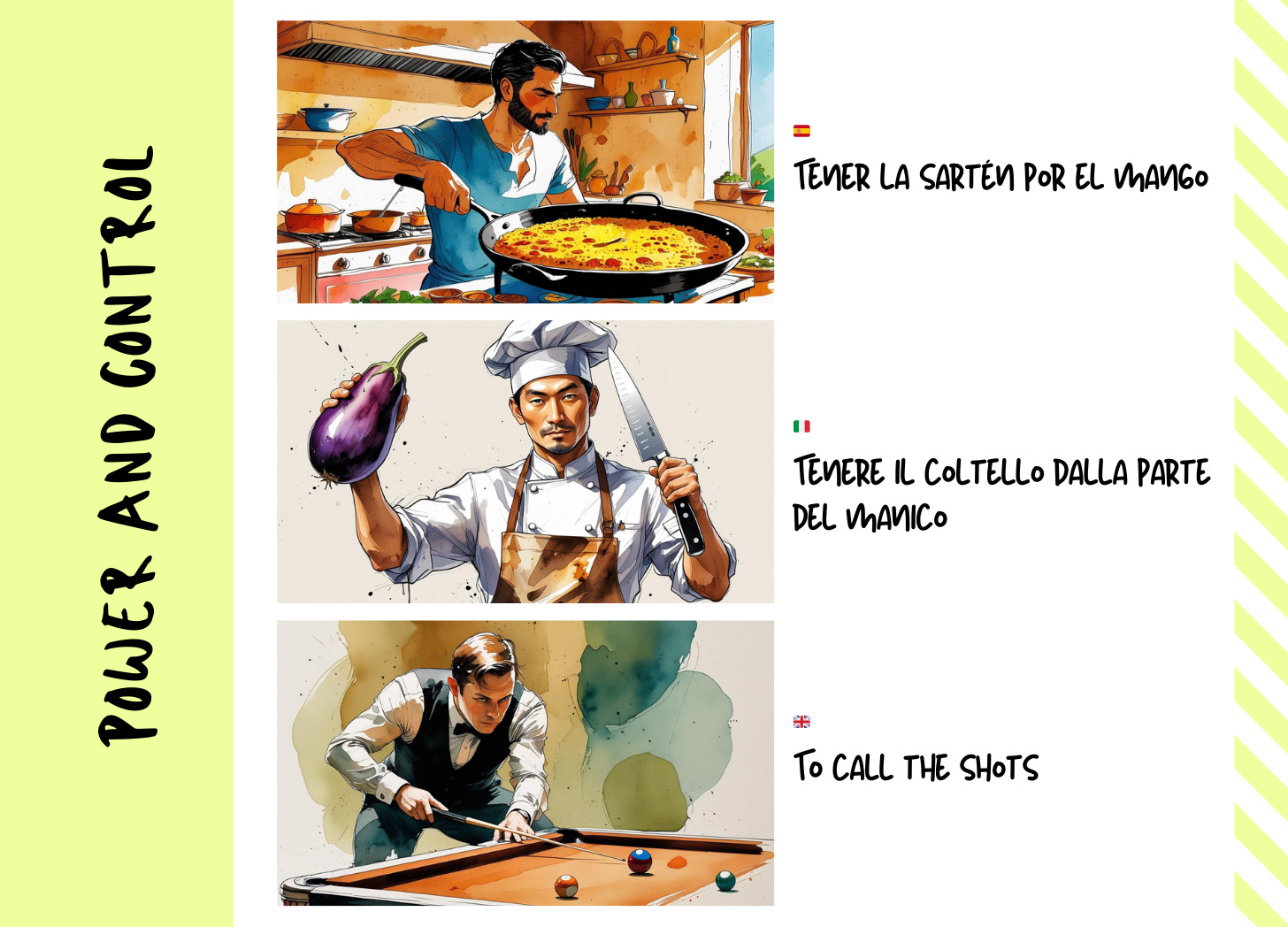

Power and control

Spanish: Tener la sartén por el mango (‘To have the pan by the handle’)

When you're holding a frying pan by its handle, you control everything: where it goes, how it moves, what happens to whatever's cooking inside.

The metaphor: Having control is like properly holding a tool.

The logic: Good grip on the handle = good grip on the situation. Kitchen mastery represents broader competence and authority.

Modern use: Applied to any situation where someone has the upper hand.

Italian: Tenere il coltello dalla parte del manico (‘To hold the knife by the handle’)

The metaphor: Similar to the Spanish one.

Why a knife? The image of the knife adds even more force to it because it directly correlates control with physical, and even violent, action.

The tone: the metaphor is used in a non-violent tone in daily situations (discussions, arguments, negotiations, and so on).

English: To call the shots

Origins: There are a number of theories regarding the origin of this idiom, including the military context, referring to gunshots hitting targets, and snooker/pool, when a player called their shot, by stating which ball they planned to hit into a pocket.

There are also references to players’ shots being called in the sport curling, in 1500s Scotland, when they were instructed on how fast, far, etc., they should take their shot.

Metaphor: Warfare and sports symbolise competitiveness, the power struggle and being the winner/victor, i.e. the one in control.

Difficult situations

Spanish: Estar entre la espada y la pared (‘To be between the sword and the wall’)

Imagine being trapped with a sword threatening you from one side and a solid wall blocking escape on the other. That's exactly how this expression makes you visualize impossible choices.

The metaphor: Difficult decisions feel like physical entrapment.

The scenario: No matter which way you move, you face danger or obstacles.

Historical context: Medieval warfare imagery, but the feeling of being "cornered" is universal.

Italian: Essere tra l’incudine e il martello (‘To be between the hammer and the anvil’)

The metaphor: In the Italian version, too, the idea of a difficult decision is conveyed through a physical constriction.

The scenario: We’re again in the Middle Ages, in the workshop of a blacksmith forging a sword!

English: To be [caught] between a rock and a hard place

Origin: It’s suggested that this idiom comes from the mining industry in early 20th century America. Miners faced the tough choice between working in difficult conditions in the mine (the rock), or being unemployed and living in poverty (the hard place).

Metaphor: Making tricky decisions feels like being trapped.

Cultural difference: The English version is quite similar to the Spanish and Italian expressions, but with the different context of mining for the same idea of making difficult choices.

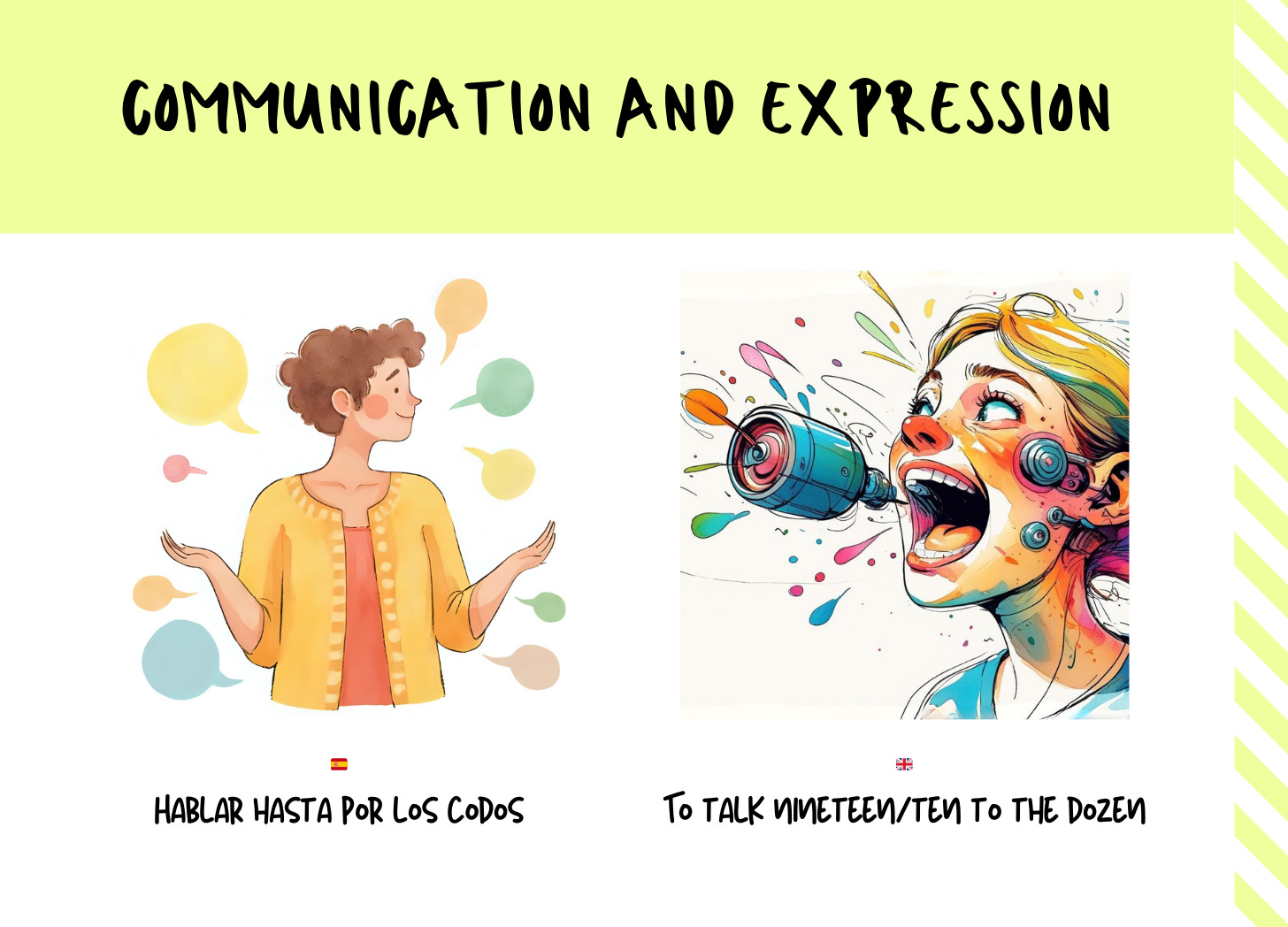

Communication and expression

Spanish: Hablar hasta por los codos (‘To talk even through the elbows’)

Picture someone talking so much that words are practically coming out of their elbows! This wonderfully absurd image captures excessive chattiness.

The metaphor: Too much speech overflows from normal boundaries.

The image: Speech normally comes from your mouth, but someone who talks excessively has so much to say it seems to emerge from everywhere, even their elbows.

Why elbows? The unexpected body part makes it humorous while emphasizing how abnormal the behavior is.

Italian: Non sputa mai (regional - ‘They never [stop to] spit’)

The context: There’s actually no general Italian counterpart to this one, but a good option is this regional expression, used especially in Central and Southern Italy.

The image: It expresses the idea of someone being so busy talking that they never take a break, not even to get rid of saliva!

The tone: It’s highly descriptive and definitely comical, exactly like the Spanish one.

English: To talk nineteen/ten to the dozen

The logic: The English variation emphasises somebody being very talkative, by using nineteen words, when just twelve would be enough. However, these days this idiom isn’t used so much.

Other common terms: These days, “motormouth” and “chatterbox” are often used to describe somebody who speaks a lot.

Tone: Chatterbox is used in a lighthearted way to refer to a person’s chatty nature, but motormouth has more negative connotations, suggesting that someone is too loud, annoying, etc. when they speak.

Spanish & Italian: No tener pelos en la lengua / Non avere peli sulla lingua (‘To not have hairs on the tongue’)

Think about how rough hair would feel on your tongue. It would make speaking clearly pretty difficult! So having no hairs means your words come out smooth and direct.

The metaphor: Speaking honestly is like having no physical obstacles in your mouth.

The logic: Smooth tongue surface = smooth, unimpeded communication.

Cultural value: Spanish appreciation for directness and authentic expression.

English: To not mince your words

The metaphor: Communication is likened to the process of mincing meat, such as to make burgers, in which the meat is broken down into small pieces.

Logic: In this context, not mincing your words means there is nothing breaking down or interfering with communicating your point across in an honest and direct way.

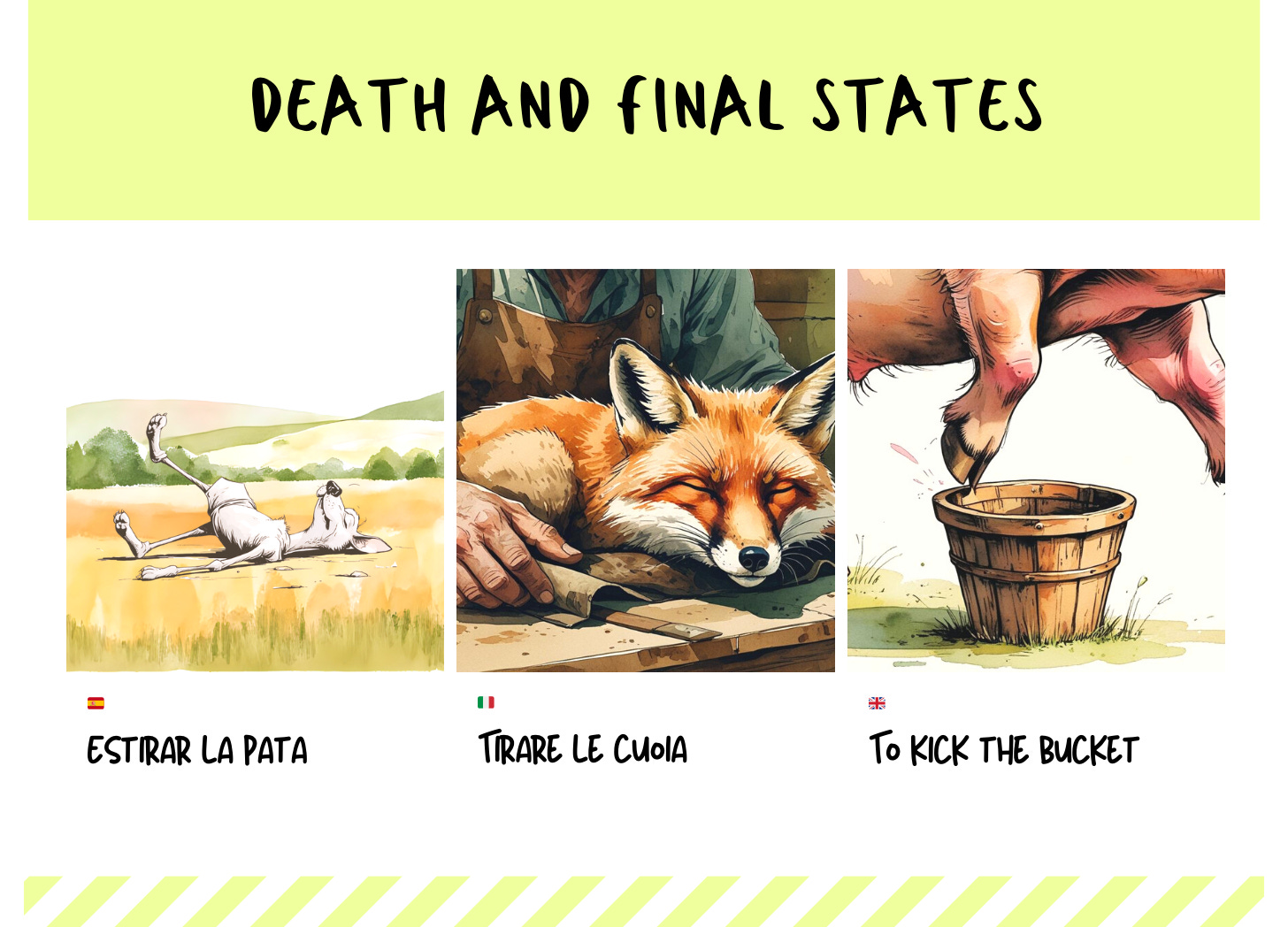

Death and final states

Spanish: Estirar la pata (‘To stretch the paw’)

This expression comes from observing what actually happens to animals (and people) when they pass away. Limbs often extend as muscles lose control.

The metaphor: Death is understood through its visible, physical signs.

Why "pata"? Using the animal word (“pata” → paw/leg) rather than the human "pierna" creates euphemistic distance. Makes discussing mortality less direct and emotionally intense.

The tone: Slightly humorous, which may be considered characteristic of Spanish cultural approach to difficult topics.

Italian: Tirare le cuoia (‘To pull the hides’)

The context: stirare le zampe (to stretch the paw) exists in Italian, too, but it’s a bit vintage and less common today.

The metaphor: the reference is to the skin of dead animals, which is pulled under their death.

Tone: the same informal, ironic tone.

English: To kick the bucket

Possible origin: One of the theories of this idiom is also animal-related, but a more gruesome one.

Historical background: “Bucket” in this case was an old name for a wooden beam, which animals were suspended from, in order to be slaughtered for meat. During this process they would have struggled and “kicked the bucket”.

Tone: This euphemism is also used in a humorous way, to avoid directly referring to human death, despite its more sinister origin.

What these patterns reveal

When you look across all these expressions, you start noticing some interesting things about how Spanish, Italian, and English handle metaphorical thinking:

Shared origins: Take Spanish "No tener pelos en la lengua" and Italian "Non avere peli sulla lingua." They're basically the same expression. This makes sense given their shared Latin roots, and it shows how some metaphorical expressions can survive centuries of separate development almost unchanged.

Same idea, different images: In several of these examples, you see the three languages using the same basic approach but choosing different concrete details. Spanish and Italian both understand control through proper tool handling, but Spanish goes with kitchen imagery (the pan) while Italian picks something with more edge (the knife).

For tough situations, all three languages understand that difficult choices feel like being physically trapped, but they use very different imagery. Spanish and Italian both draw from medieval metalworking—Spanish chooses sword and wall, while Italian pictures hammer and anvil. English shares that underlying trapped feeling but pulls from completely different territory: mining imagery with rock and hard place rather than medieval weapons.

Big differences: Other times, languages take entirely different routes to the same destination. Spanish treats excessive talking as physical overflow from the body ("through the elbows"), while English makes it about mathematical excess ("nineteen to the dozen").

Bodies, tools, and physical experience: Many of these expressions connect abstract concepts to physical experience, but with surprising variety in which physical areas they choose. We see spatial positioning, tool use, body function, food prep, and animal behavior all serving as raw material for understanding complex ideas like control, honesty, or death.

If you're learning any of these languages, recognizing these patterns helps in practical ways.

Firstly, understanding that many everyday expressions involve these kinds of metaphors makes you more aware of how differently languages can express abstract concepts. You naturally start paying attention to these details, which prevents you from trying awkward literal translations. For instance, you won't attempt to say someone is "talking through their elbows" in English because you realize it represents a completely different conceptual approach.

You also start noticing that many expressions actually use the same basic underlying metaphors, even when the concrete elements vary. When you encounter Italian "essere tra l'incudine e il martello", knowing it shares that trapped-feeling concept with English "between a rock and a hard place" helps you get the meaning quickly. Furthermore, trying to picture the metaphor behind the expression helps you understand and remember it.

In short, understanding these metaphorical connections—this "metaphor awareness" we mentioned earlier—helps expressions stick because you're tapping into the logic that makes them meaningful rather than just memorizing arbitrary phrases. You develop a sensitivity to the different ways of thinking about the same human experiences, and that's undoubtedly one of the most rewarding aspects of learning a new language.

Thanks for the restack, @bnjd!

One time I heard the phrase "raining cats and dogs"...and I was like What? 🤔 Wonderful post 🌹♥️.